The Amazonian Coloring Book

The story of a social venture in Peru that empowered female artisans and turned their ancestral art into a coloring book that dramatically improved their livelihoods and created a platform to foster their culture.

Venture: Koshi Studio

Domain: Indigenous Art & Culture, Social Innovation

My role: Research Lead | Team: Product designer, Environmentalist

Skills: Explorative research, participatory design, evaluative research, product strategy

Timeline: May 2020 - August 2020TL;DR

Problem space

In 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak caused Cantagallo to have the highest infection rate in the country. This neighborhood, located in Lima, Peru, is home to 240 families from the Shipibo-Conibo indigenous community. Due to pandemic restrictions, Shipibo-Conibo artists who rely on selling handmade artisanal products at ambulatory and crafts fairs, experienced a complete halt in sales, which had a severe impact on their financial income.

My contributions

As a co-founding member of Koshi Studio, I contributed to setting the vision and general management of the venture - including marketing, sales, public relations, and legal.

As the Research Lead of the Amazonian Coloring Book, I defined and executed a research strategy that encompassed explorative, generative, and evaluative research techniques, to guide and enhance product development processes.

I employed a combination of qualitative research methods such as contextual inquiries and semi-structured interviews. I designed and moderated co-creation workshops with indigenous artisans. Additionally, I synthesized and analyzed data to inform product design decisions. Furthermore, I created evaluative tools through surveys and interviews to assess product specs and market fit.

Outcome

Our team's creation, the Amazonian Coloring Book, is more than just a coloring book. By featuring 30 beautiful Shipibo-Conibo designs repurposed from unsold art pieces, the book has given these artisans a platform to share their stories and culture while also supporting them financially. This has resulted in a sustainable income inflow based on the royalties from the rights of their art, improving their monthly income by 54% for every 50 books sold. In just the first few months, we sold over 1,000 books.

Not only does this product support artisans financially, but it also empowers them psychologically by helping them regain confidence in the value of their work and art. This initiative raises visibility of their heritage and culture with the rest of the world. Finally, this initiative also benefits buyers by providing an art therapeutic process that works as a perfect companion in stressful times, helping to alleviate the stress caused by the pandemic through a cultural and educational experience.

Due to the impressive reception of the Amazonian Coloring Book, our team decided to broaden the scope of the project by including more artisanal indigenous communities across the country and expanding the range of available products.

Design challenge

How might we support Shipibo-Conibo artisans finding financial stability and maximizing the effort and value of their art during the pandemic?

Design process

We conducted exploratory research through contextual inquiries and semi-structured interviews to better understand the pain points and problem space faced by Shipibo-Conibo artisans. This understanding defined our design direction and inspired our design challenge.

We fostered agency and involvement in the process by conducting an ideation workshop with the artisans, down-selecting ideas based on relevance, feasibility, and market saturation, and finally settling on a coloring book as the final idea.

We prototyped and distributed the coloring book to target users, collecting feedback through interviews and a survey to gather descriptive data on product market space and desirability. The feedback was integrated into the final prototype and the product was launched.

After its release, we continued to gather feedback through surveys to identify opportunities for improvement and future products.

scroll to read the full case study!

〰️

scroll to read the full case study! 〰️

Context

Peru is home to over 50 indigenous communities that, in addition to their immense cultural value, share a significant activity: craftsmanship led by women. Most artisanal communities live in extreme poverty, relying on crafts as a vital income source. The COVID-19 outbreak in Peru halted social mobilization and tourism, leading to stagnation in their sales.

In 2019, we co-founded Koshi Studio in Lima, Peru as a platform to reduce the socioeconomic gap between indigenous and artisan communities by co-creating original products inspired by the artistic skills that make up their ancestral heritage.

Through an empathetic and collaborative approach, we seek to understand the layers affecting the problem that hundreds of indigenous artists face: sales stagnation, due to the lack of market fit of their products. In this case study, we will expand on the design process of this successful product and my approach as a Research Lead.

From the jungle to the city

The Shipibo-Conibo are an indigenous community located in the central jungle of Peru. The migration of the first Shipibo-Conibo to Lima, Peru’s capital city, began in the 90s. Years later, their settlement in Cantagallo took place in groups, all of them with the aim of seeking better living conditions and opportunities for work and study. Cantagallo currently hosts 240 families and is considered Peru’s first indigenous urban community. Some of the challenges they face include inequality, social exclusion, and poverty.

Shipibo-Conibo Art and Kené

Shipibo-Conibo, especially women, found a means of subsistence and the main source of income for themselves and their families in the making of handicrafts. For the Shipibo-Conibo, art constitutes a space for expression, personal development, encounter, and social participation that allows people to transcend physical, relational, economic, and communication barriers and difficulties. Research has found that artistic expressions can be used as a tool to transform and generate changes at the individual and collective level, especially for the empowerment and capacity for the participation of people and communities in circumstances of vulnerability and social exclusion.

During 2020’s COVID-19 outbreak, Cantagallo became the neighborhood with the highest number of infections per square meter in the country.

Shipibo-Conibo artists’ main source of income relies on the handmade artisanal products they produce and sell at ambulatory and crafts fairs. When the pandemic restrictions were implemented, their sales were completely paralyzed due to social immobilization. These conditions deeply jeopardized the financial income.

The Problem

“It took me 3 months to finish this mantle. Given the pandemic, it's been over 2 weeks and I still can't sell it.” - Olinda Silvano

Objective

Our design challenge was clear:

How might we support Shipibo-Conibo artisans finding financial stability and maximizing the effort and value of their art during the pandemic?

Ethical Considerations

When collaborating with an indigenous population, our whole team was aware of and followed several ethical considerations.

-

We were sensitive to their cultural beliefs, values, and practices.

-

Participants were fully informed about the entire design process, including their rights and possibility of abandoning the process at any time without any repercussions.

-

We were aware of power dynamics and continuously strived to create a collaborative and equitable relationship with participants.

-

Whatever the solution would end up being, we would always respect the intellectual property rights of artisans art, and would be credited and compensated for their contributions.

Exploratory Research

Research Goals

(1) Gain insight into how Shipibo-Conibo women have adapted to the pandemic and whether their involvement in traditional crafting practices has been affected.

(2) Understand the challenges and opportunities the pandemic presents for preserving traditional artisan practices, and identify strategies that could be implemented to support their continuation.

(3) Identify key factors that contribute to successful collaboration that promotes the sustainability and well-being of artisan communities during the pandemic.

Research Questions

(1) What is the role craftsmanship plays in the everyday lives of Shipibo-Conibo women, and how has this been affected by the pandemic?

(2) How can the preservation of indigenous cultural practices and traditional artisan techniques be supported during the pandemic?

(3) What contributes to successful collaboration promoting the sustainability and well-being of artisan communities during the pandemic?

Participant Recruitment

We recruited 6 participants, all artisan women from the Shipibo-Conibo community of Cantagallo. Our inclusion criteria considered they had crafted as their main occupation.

Our initial contact started with the leader of an artisanal community, and through snowball sampling, we were able to access other women in the community.

Method selection

Given that our study approach focused on learning about the Shipibo-Conibo women’s experience with craftsmanship throughout the pandemic, I decided to prioritize the following methods:

Contextual inquiries: These involved observing and interviewing users in their natural settings, and would allow me to gain a holistic understanding of how the pandemic was impacting their lives and crafting practices. I was able to observe how the women engage in crafting, their tools and materials, and the social and cultural contexts in which they create their craftts.

Semi-structured interviews: These allowed me to provide a more personalized and nuanced understanding of their experiences through open-ended questions and probing. Moreover, these were ideal to facilitate trust and rapport building with the participants, creating a safe environment for them to share their experiences.

Overall, combining both methods would provide a comprehensive understanding of the artisans experience. Contextual inquiries would allow me to observe and gain insight into the participants’ context and environment, while also complementing it with interviews would help me get a deeper understanding of their perspectives.

Contextual Inquiries

This visit exposed to us the precarious conditions the community of the Shipibo-Conibo live in.

-

Visiting Olinda’s house helped us to better understand her family’s lifestyle, as well as the problems and needs she and her community faced.

What we learnt:

Gained insight into Olinda’s lifestyle and daily activities

Olinda’s immigration story, as well as the immigration experiences of other people in her community from the Amazon.

Shipibo-Conibo crafts are the main or only source of income artisans have to support themselves and her families.

Craftsmanship has taught the artisans to thrive, not only economically, but also emotionally as a coping strategy in the face of the adversities they have experienced. This is because, through the crafts they make, the participants find a way to share their stories, empower themselves and give their lives new meaning, developing coping strategies associated with a resilient response and a positive self-concept.

-

The warehouse is the place where Shipibo-Conibo women of all ages share while creating their crafts.

What we learnt:

In Shipibo-Conibo culture, making kené is about an activity learned even before learning to speak. An art that traditionally belongs to women.

The warehouse represents a ‘sacred’ place for them, as this is where they perform their kené, and where intergenerational knowledge exchange happens. Given the nature of the pandemic, these shared spaces and moments were restricted.

Through their kené designs, Shipibo-Conibo women share their stories, express their cultural identity. Kené keeps alive techniques and knowledge of ancestors while affirming and establishing new identities in interaction with the city.

The artistic process of artisanal products is extremely rich and complex. The colors in each mantle are carefully created by the natural pigment of different plants. Once the fabric is dyed, the ancestral kené designs are drawn handmade. Once ready, they are covered in natural mud, and after resting for a week under the sun, the fabric is heavily washed to remove all traces of mud, while preserving its pigmentation. The final step is sewing the designs by hand, which takes up to 2 months.

The participants were concerned given how months worth of work were stagnated due to the lack of tourism and mobilization.

Semi-structured Interviews

The semi-structured interviews with our participants took place after the contextual inquiries. The purpose of the semi-structured interviews was to gain a more personalized and nuanced understanding of their experiences. In addition, I wanted to learn about their perceptions of what a potential collaboration would look like.

A subset of the relevant prompts I selected include:

Role of craftsmanship for women in the Shipibo-Conibo community.

Experience and relationship with craftsmanship before the pandemic.

Impact and challenges of the pandemic in their crafting practices.

Opportunities to support preservation of indigenous craftsmanship.

Insights

In order to make sense of our next step, I categorized a large volume of notes taken from the contextual inquiries that were realized, as well as the interviews through a thematic analysis. Consequently, I crafted three core insights.

-

Although it was the first time everyone was experiencing the adversity of a global pandemic, artisans shared other challenges as they immigrated from the Amazon to the city. Through hard times craftsmanship and elaborating their kené designs serve as a coping mechanism.

-

Kené keeps alive techniques and knowledge of ancestors while affirming and establishing new identities in interaction with the city. Moreover, it materially connects them with recognition as a group.

“Just by seeing the kené people from the city can say we are from the Shipibo-Conibo family, we are from the Amazon, and it feels like we still belong to the culture. We are proud that they recognize us for our craft, our kené.” - S

-

Shipibo-Conibo sales were completely paralyzed due to the absence of tourism and mandatory immobilization caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The artists had a collection of high-value products without being sold and as a result, they started doubting their talent and the worth of their work.

In the following section, I will elaborate on the initial collaborative design process we followed to land our first prototype for the Amazonian Coloring Book.

Prototyping

Design Opportunities

Considering the target audience we were going to tailor our products to, we conducted desk research to learn more about how Peruvians were experiencing the pandemic. Studies in early 2020 showed that 31% of the Peruvian population was evidencing higher stress levels than ever before.

There was an opportunity to develop a product that responded to the need for recreation of Peruvians in the face of stress exacerbated by confinement.

Ideation & Participatory Design

We design collaborative sessions with artisans given that it was a main priority to involve them in the design process incorporating their knowledge, values, and perspective in the product ideation phase. Considering the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, our ideation process was carried via Zoom workshops.

-

After an introduction, where we reminded them of the context and set out some participation rules, we started by setting our goals together. We wanted to brainstorm product ideas to create together. We wanted artisans to visualize the potential and expression their designs could have. We proceed to map the context, understanding the environment and dynamic buyers were experiencing amidst the pandemic.

After we discussed our target audience and their context, we began our idea generation process. Both individually and collectively, started brainstorming ideas for the design product. Once the time had ran out, we started sharing and discussing the different ideas everyone brought to the table. Collectively, we came up with 50+ product ideas.

After affinitizing the product ideas in categories, we started voting. There were five products that had the biggest amount of votes: notebooks, coloring books, towels, mugs, and prints.

-

After several discussions and considering elements such as the socio-political context we were experiencing, the feasibility of production, and most importantly, the correspondence to users’ needs, we had a winner: Coloring books.

As our research stated, the Peruvian population was evidencing higher stress levels than ever before and art therapy is considered an effective resource for the reduction of stress and anxiety. We identified an opportunity to develop a product that responds to the need for recreation of Peruvians in the face of stress exacerbated by confinement.

On one hand, we would be able to reinforce the value of the artisans’ unsold work through the use of their designs. On the other hand, we would provide users with a unique cultural product that facilitated a space for art therapy given the stressful months everyone was going through. Moreover, coloring books consisted of a product that could be printed and produced at scale. This, in turn, would provide artisans with a growing and sustainable income.

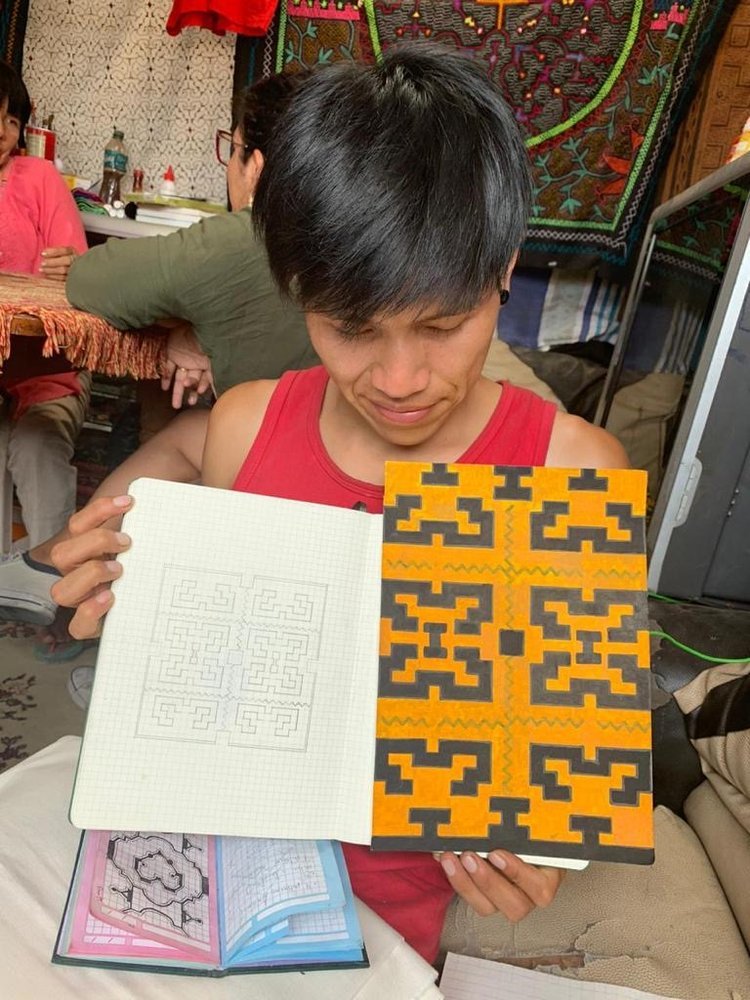

Alongside Ronin, one of the Shipibo-Conibo artisans, our first low-fidelity prototypes started sketching kené designs on paper to get a general view of how the designs of coloring books could potentially look like a coloring book.

Considering the complexity of kené designs, we opted to explore a digital vectorization process. Although vectorization was considered a manual and long process, it allowed for precise details to be included, considering the geometrical complexity of kené.

We started by vectorizing three designs: We were able to capture the existing Shipibo patterns of mantles. These prototypes would be tested with potential consumers in order to gather product feedback.

Prototyping

Vectorization Process

We decided to vectorize two designs to validate if we could capture all the details of existing Shipibo patterns in their mantles. These prototypes were tested with potential consumers in order to gather feedback.

Evaluative Research

After prototyping our idea through a digital version of the coloring book, we needed to test our concept and product with real end-users.

Survey

We developed a survey that was answered by 303 Lima citizens in the course of a week. This survey was distributed evenly between participants of diverse genders, ages, and locations in Lima.

-

Identify competitors in the market and learn about users’ previous experiences buying coloring books.

-

Learn the design, quality, and content expectation of users’ in regards to a coloring book.

-

Evaluate users’ feedback on the concept and design of the book based on the prototypes.

-

Explore the appeal of the product to potential users, as well as additional motivations to purchase the product.

-

Learn about the estimated price users’ would deem appropriate for the product.

Semi-structured Interviews

After analyzing the answers from the survey, and considering sociodemographic variables, we developed a segmentation of potential customers. The segments were composed of users that had owned and enjoyed coloring books. They were segmented by age:

Recently graduated students

Young adults

Adults / Parents

Elder population / Grandparents

Additionally, we included users that were not motivated by the coloring books but had a purchase intention due to their social impact.

We proceeded to send copies of our prototype version for them to interact, feel, and use the book before our interview with them.

Interview topics

Shopping patterns

Experience with coloring books

Product feedback

Shipibo-Conibo context

Research Findings

Feature-specific feedback

-

Users value having a wide range of designs to cater to their personal preferences. Users may be looking for designs that are simple and minimalistic, or more intricate and complex depending on their mood. Moreover, we’re planning that immersing in the Amazonian Coloring Book will be an experience that can be individual, and also shared with others. Therefore, offering a diverse range of designs can cater to different age groups sharing the experience.

“I’d like to see both complicated geometric and simple designs, so I can pick the one I like according to the occasion and my mood.” - P3

Data Point: More than 70% of surveyed participants listed the variety of designs as the second most important attribute.

-

We learnt users are motivated to purchase a product that has a social purpose or contributes to a cause, as they feel that through their purchase they are making a positive impact on society. This also showed that users may feel compelled to purchase the book even if they don’t have a particular interest in coloring.

“Although I don’t color often, I’d buy the product due to the component of social help. Difficult times like these ones are when we need to help the most.” P2

Data Point: 30% of surveyed participants expressed interest in the product solely due to its social purpose

-

Users are interested in the backstory and cultural significance behind the artwork they are purchasing. Curiosity aroused particularly around the artist’s creative process, inspiration, and journey towards becoming an artist. Additionally, although most users were unaware of the Shipibo-Conibo community, there was great interest to learn about their culture, and the symbolism of the art work.

“I’d be interested to learn how they became artists, as well as the medium of art they enjoy the most. I’d also love to learn about the meaning of the kené iconography.” -P5

Insights

The Amazonian Coloring Book

Taking into account all insights and feedback, we were able to curate a coloring book that was co-created with users and artisans. The Amazonian Coloring Book is a medium to diffuse the Shipibo-Conibo culture, introducing readers to their personal stories as artisans, and collective memories as a Community.

This high-end book is composed of 5 chapters, and every chapter is a tribute to each one of the artisans, including information about their cosmovision and relationship with art.

This product shares an in-depth explanation of their kené (design in Shipibo). As well as their beautiful kené designs ready to be colored. The book has 30 designs in total, six unique kené designs per artisan. Additionally, we enhanced the experience by including the following value proposition:

The Product Specs

The book serves as a platform for artisans to share their personal stories, as well as their meaning and relationship with art, a highly requested piece of information requested by users, and an important goal for artisans.

”Since I was a child I learned to do kené thanks to my ancestors, my grandparents, through ‘piri piri’ and through the vision of ayahuasca. Kené was very important in my life because it helped me to empower myself as a woman and to take my art to many countries, visiting cities, leaving my mark and that of my grandparents and their inherited knowledge.”

Storytelling

Considering our commitment to the environment, we wanted to be able to give the designs in the book a second life. For that reason, we integrated an easy-to-tear-off pattern in all of the pages of the book. Thus, users are free to use their designs like posters, cards, or even wrapping paper, as some of them suggested during the interviews. Following user feedback, this is communicated explicitly at the beginning of the book.

Upcycling Desings

Considering the wide age ranges in the target audiences that we learned would be interested in our product from our surveys and interviews, we decided to include, although subjective, a variety of designs in terms of difficulty and style. Complemented by the tearable nature of pages, the Amazonian Coloring Book is a product designed to enjoy individually or collectively.

A shared experience

Impact

Koshi Studio significantly increased featured artisans’ monthly income, successfully fundraised donations to benefit 400+ indigenous families, and was recognized in several media platforms fostering ancestral art and culture.

Over 1K books were sold between September and December 2020, successfully representing a 54% monthly income increase per every 50 books sold.

Fundraised $15k+ to benefit 400+ indigenous families during the COVID-19 outbreak. Our work was recognized by the National Institute of Civil Defense

The Amazonian Coloring Book was presented in a Culture and Literature event hosted by the Municipality of Lima and in a webinar that featured the artists.

The Amazonian Coloring Book story was featured in Peru’s most renowned newspaper, El Comercio, as well as Caretas and PuntoEdu.

After the Amazonian Coloring Book was published and hundreds of copies were sold and distributed nationwide, we continued to conduct feedback with our customers.

Every time we sold the product directly, we would invite customers to fill out a feedback survey. Through this survey, we learned about their perception of the attributes of the book, their motivation to purchase the book, how they learned about the product, the things they liked the most, and the ones they disliked or would change.

Some of the things we learned included gaining a deeper knowledge of the artists, including different communities per book and visualizing their geographical locations through a map.

Aftermath

Gathering continuous feedback

Given the successful collaboration with the Shipibo-Conibo and the positive impact the project had on them educationally and economically, we looked for other artisan communities in Peru experiencing a similar situation post-pandemic. We wanted to upscale our design process to impact more people.

Upscaling the design process

Reaching other communities

After experiencing the entire design process with the Shipibo-Conibo community, we were able to meet Rita Suaña, the president of the association of artisans of the indigenous community Uro. The Uro is a community of approximately 2000 inhabitants who inhabit the floating islands of Lake Titicaca.

Expanding our product portfolio

Through the successful product development of the coloring books, we were able to learn about an efficient end-to-end design process, as well as our customers’ main demographics.

Learnings & Reflections

-

It's crucial to acknowledge our biases when collaborating with indigenous artisans. As outsiders, we subconsciously carry assumptions and preconceptions about their culture, which can impact our approach and communication with them.

-

We were self-aware and recognized the power dynamic in our relationship, as we hold some of the resources and opportunities that the artisans may depend on. We approached collaboration with respect, sensitivity, and a willingness to learn from their perspective.

-

By working hand in hand with artisans, we developed a product that was more authentic and reflective of their cultural values and traditions. It also created a sense of ownership and pride among the artisans, through their active contributions to the final product.

Through this process we recognized their skills, knowledge, and creativity and empowered them to take an active role in the design process.

-

When asking artisans to share about their stories, we relied on open-ended questions and some of them felt shy to respond - which resulted in brief descriptions of each artisan in the book.

Looking back, I would have experimented with other ways to talk in their language, like for example asking them to share their stories through their art as they usually do.